Jeff Lynne: «No hacíamos pop descerebrado. Era pop inteligente»

Hace más de dos años, Dorian Lynskey realizó a JEFF LYNNE una entrevista para Billboard que hoy traemos a nuestra web, porque la consideramos interesante para cualquier fan de ELO/JEFF.

Electric Light Orchestra saldó una deuda pendiente: finalmente ingresó al Salón de la Fama del Rock & Roll, junto con Pearl Jam, Journey, Joan Báez, Tupac Shakur y Yes. Con esa excusa, compartimos esta entrevista a Jeff Lynne, que repasó algunos momentos claves de su carrera.

No existe leyenda del pop más serena y frontal que Jeff Lynne. Sentado en la biblioteca de un venerable hotel londinense, con su agradable acento de Birmingham, Inglaterra, intacto a pesar de vivir hace 20 años en Beverly Hills (luego de dos matrimonios, está saliendo actualmente con Camelia Kath, la exesposa del actor Kiefer Sutherland), todavía guarda el look de un extraordinariamente próspero plomo de los años 80: pelo desgarbado, barba y anteojos de sol.

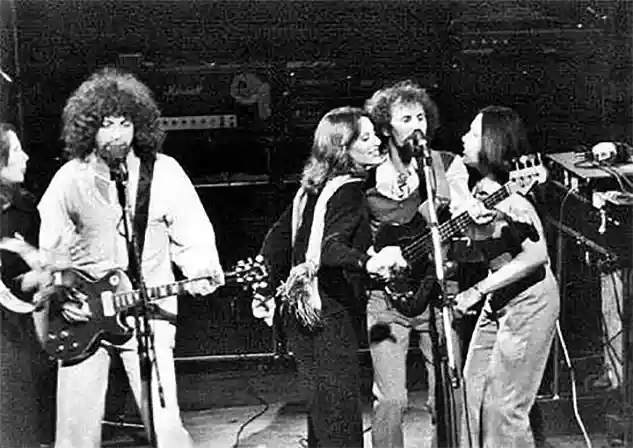

La normalidad genial de Lynne, de 69 años, significa que nunca fue una estrella del pop exactamente, aun cuando Electric Light Orchestra (ELO) –la banda que formó como único compositor y productor en 1970– estaba en la gloria con su cuarteto de cuerdas. ELO impuso 18 singles en el Top 40 del Billboard Hot 100. Entre 1972 y 1986, llenó estadios y dominó un estilo de pop anhelante, opulento y retro futurista, cuyos fans incluyen a Daft Punk, The Flaming Lips, el director David O. Russell y Ed Sheeran, con quien Lynne hizo un dueto en los Grammy 2015.

Cuando Lynne disolvió ELO en 1986, felizmente se mudó a la silla de cocompositor/productor para gente como Tom Petty, Roy Orbison y los tres Beatles restantes, convirtiéndose también en el miembro más modesto del supergrupo babyboomer The Travelling Wilburys, compartiendo cartel con Petty, Orbison, Bob Dylan y George Harrison.

En 2015, regresó como Jeff Lynne’s ELO con el lanzamiento de su primer álbum en 14 años, Alone in the Universe– como la más reciente sorpresa agradable en una carrera llena de ese tipo de cosas. “Obviamente todo el mundo está saliendo a hacerlo si puede –sostiene–, y yo tuve la suerte de hacerlo bien”.

¿Cómo definirías sintéticamente a ELO?

– Una banda normal con dos chelos y un violín. Las cuerdas generalmente acoplaban porque no había micrófonos en esos días. Solían correr por todo el escenario como locos, tocándolos en pleno vuelo, así que la afinación era un espanto, pero era un buen espectáculo. Daban vueltas por ahí con esos pinches gigantescos al final del escenario, es una sorpresa que nadie haya terminado atravesado.

ELO está de moda otra vez ahora, pero ¿cuándo fue que estuvieron lo más lejos de eso?

– Diez o quince años atrás. Queríamos hacer un par de shows, pero no había interés. Todo eso cambió en los últimos seis años. Creo que un montón de personas se dieron cuenta de que lo que estaba haciendo no era pop descerebrado. Era pop inteligente.

¿Cuándo te diste cuenta de que podías escribir un hit?

– Supongo que habrá sido con 10538 Overture [en 1972]. Estaba complacido con eso. Recuerdo haber pensado “Wow, realmente puedo escribir un tema”, porque no me creía capaz. Los discos de mi vieja banda, The Idle Race, no habían logrado mucho, excepto con los pocos fans más leales. Después, creo que Evil Woman [en 1975] fue “el” tema. Lo escribí tan rápido. Ahí fue cuando entendí de una vez cómo es la producción y la composición.

Cuando ELO estuvo en su punto más álgido a fines de los 70, ¿te preocupó que no tuvieras la personalidad para ser una estrella pop propiamente dicha?

– Probablemente. Porque no lo era y porque no pretendía serlo. No me considero estrella, sino cantautor, vocalista, productor y guitarrista. Puedo cantar bien, y también escribir temas.

Se sabe que odiabas tocar en vivo. ¿Era por el show o por todo lo demás que venía con eso?

– Sonaba para la mierda, ese era el problema. Los equipos de todos en ese entonces eran basura. Soy un productor, así que me puedo poner exquisito. No era malo… lo hago sonar como si hubiera sido espantoso. Simplemente no era lo que yo quería hacer.

¿Qué pasó con la nave espacial gigante que usaron en la gira de 1978?

– Creo que fue desarmada al final de la gira. Habría costado cientos de miles mantener la maldita cosa. Era un monstruo enorme. Era un poco un dolor de cabeza, realmente, porque tomaba dos días llevarlo de un lugar a otro, con lo que tendrías que hacer el show siguiente sin ella, y por supuesto la gente diría “¿Dónde está el platillo volador?”. Me imagino que estarían un poco desilusionados.

¿Alguna vez anduvo mal?

– Sí, cada tanto. Estábamos todos sobre plataformas hidráulicas y aparecíamos a través del escenario, pero alguna que otra vez se atascaba y lo único que podían ver era tu cabeza. “¡Sáquenme de aquí!”. Realmente vergonzoso.

Q Magazine nombró Livin’ Thing como su mayor “placer culposo”. ¿Te molesta ese concepto?

– Sí, porque en realidad es un tema muy inteligente. Pasa por dos relativas menores de un saque. No ves muchas así. Me gustaba el pop. No me gustaban las idas y vueltas pretenciosas de las canciones de 20 minutos de principios de los 80. Quería hacer temas lindos y concisos de tres minutos que tuvieran un buen sonido. El pop es para mí una de las formas más fuertes de la música, porque es tan difícil escribir una melodía que siga vigente luego de 40 años.

En Discovery, de 1979, abrazaron con éxito la música disco. ¿Alguna vez fuiste a los boliches?

– Sí, fui una vez a Studio 54 [célebre disco de Nueva York]. Estaba bien, supongo. Estaba lleno de estrellas de cine y ese tipo de gente. Me gustó el cuatro por cuatro, básicamente. El bombo haciendo bang, bang, bang, bang.

¿Qué canción fue la que te dio más dinero?

– Probablemente Mr. Blue Sky. Ha estado en un montón de películas, y pagan fortunas. Cuando la escribí [en un chalet suizo] había habido mucho niebla, y estaba arriba en la montaña. No había podido ver nada por una semana ni armar ningún tema. Después salió el sol, y escribí Mr. Blue Sky como un chiste. Resultó ser una muy linda canción.

Cuando disolviste ELO en 1986, ¿la idea era moverse hacia la producción?

– No tenía nada planeado particularmente, pero George Harrison me contactó y me pidió que produjera su álbum Cloud Nine. Tom Petty se enteró y me frenó en la calle en Los Ángeles y me dijo: “Ey, Jeff. ¿Te gustaría que escribamos canciones juntos?”. Descubrí que podía ser un gran colaborador. No era como lo imaginaba. Y por supuesto Full Moon Fever fue un gran, gran éxito. Sigue siendo el álbum favorito que hice.

¿Cuál de los miembros de The Travelling Wilburys contaba los mejores chistes?

– Roy Orbison. Tenía la risa más maravillosa que escuché. Era aguda, así que era como una risita. Podía hacer un sketch de Monty Python él solo, todas las partes, y después se caía riéndose de sí mismo.

Cuando te pidieron que produjeras el “nuevo” single de los Beatles Free as a Bird en 1995, ¿tuviste que callar al fan interno y dejar que el profesional se haga cargo?

– Siempre voy a ser el fan. Nos pasamos todo el primer día recordando, solo George, Paul [McCartney], Ringo [Starr] y yo, sentados alrededor de una mesa riéndonos, contando historias de los viejos tiempos. Las cuales no puedo contar, por supuesto. Algunas eran groseras. El solo hecho de estar ahí fue suficiente. Lo otro daba un poco de miedo. Hacer un disco de un cassette con la voz y el piano de John [Lennon] pegados juntos en mono. Lo hice a las dos o tres de la mañana porque no quería arruinarlo y que ellos estuvieran diciendo “Ja, ja, ¡no podés!”. Al día siguiente Paul vino corriendo y me dijo “¡Lo lograste! ¡Bien hecho!”, y me dio un gran abrazo. Fue lo mejor que podría haber pasado.

¿Es cierto que en 1968 fuiste testigo de la grabación del White Album de los Beatles?

– Sí, eso fue de lo más raro. Vi a Paul y a Ringo en el Estudio Uno haciendo Why Don’t We Do It In The Road. Y de ahí me fui al Estudio Dos y podía escuchar este tema que sonaba increíble. Era Glass Onion. Entramos, éramos el baterista de The Idle Race y yo. John y George nos saludaron. Y del otro lado de la ventana estaba George Martin, saltando de aquí para allá conduciendo las cuerdas. No pude dormir por semanas después de eso.

¿Tu madre nunca te dijo que es de mala educación usar anteojos de sol en interiores?

– No, lo que dijo fue “Parecías un desastre en la televisión”, y entonces inmediatamente me puse los anteojos porque no quería ser eso. Había estado toda la noche tomando, supongo. Siempre hablaba de las bolsas de mis ojos. Por eso siempre los uso. La gente debió pensar “Se convirtió en un idiota ostentoso con sus anteojos de sol a la noche”, pero no era por eso. Simplemente no quería mostrar mis bolsas.

When I Was a Boy (2015) describe tus sueños de chico de convertirte en un músico. ¿Conseguiste todo lo que querías?

– Sí, en cierto modo. Es como medio raro conseguir todo lo que querés. Y ha pasado a lo largo de los años. Todo lo que quise ha venido hacia mí: los Wilburys, los Beatles… así que es fantástico. No podría pedir más.

No existe leyenda del pop más serena y frontal que Jeff Lynne. Sentado en la biblioteca de un venerable hotel londinense, con su agradable acento de Birmingham, Inglaterra, intacto a pesar de vivir hace 20 años en Beverly Hills (luego de dos matrimonios, está saliendo actualmente con Camelia Kath, la exesposa del actor Kiefer Sutherland), todavía guarda el look de un extraordinariamente próspero plomo de los años 80: pelo desgarbado, barba y anteojos de sol.

La normalidad genial de Lynne, de 69 años, significa que nunca fue una estrella del pop exactamente, aun cuando Electric Light Orchestra (ELO) –la banda que formó como único compositor y productor en 1970– estaba en la gloria con su cuarteto de cuerdas. ELO impuso 18 singles en el Top 40 del Billboard Hot 100. Entre 1972 y 1986, llenó estadios y dominó un estilo de pop anhelante, opulento y retro futurista, cuyos fans incluyen a Daft Punk, The Flaming Lips, el director David O. Russell y Ed Sheeran, con quien Lynne hizo un dueto en los Grammy 2015.

Cuando Lynne disolvió ELO en 1986, felizmente se mudó a la silla de cocompositor/productor para gente como Tom Petty, Roy Orbison y los tres Beatles restantes, convirtiéndose también en el miembro más modesto del supergrupo babyboomer The Travelling Wilburys, compartiendo cartel con Petty, Orbison, Bob Dylan y George Harrison.

En 2015, regresó como Jeff Lynne’s ELO con el lanzamiento de su primer álbum en 14 años, Alone in the Universe– como la más reciente sorpresa agradable en una carrera llena de ese tipo de cosas. “Obviamente todo el mundo está saliendo a hacerlo si puede –sostiene–, y yo tuve la suerte de hacerlo bien”.

¿Cómo definirías sintéticamente a ELO?

– Una banda normal con dos chelos y un violín. Las cuerdas generalmente acoplaban porque no había micrófonos en esos días. Solían correr por todo el escenario como locos, tocándolos en pleno vuelo, así que la afinación era un espanto, pero era un buen espectáculo. Daban vueltas por ahí con esos pinches gigantescos al final del escenario, es una sorpresa que nadie haya terminado atravesado.

ELO está de moda otra vez ahora, pero ¿cuándo fue que estuvieron lo más lejos de eso?

– Diez o quince años atrás. Queríamos hacer un par de shows, pero no había interés. Todo eso cambió en los últimos seis años. Creo que un montón de personas se dieron cuenta de que lo que estaba haciendo no era pop descerebrado. Era pop inteligente.

¿Cuándo te diste cuenta de que podías escribir un hit?

– Supongo que habrá sido con 10538 Overture [en 1972]. Estaba complacido con eso. Recuerdo haber pensado “Wow, realmente puedo escribir un tema”, porque no me creía capaz. Los discos de mi vieja banda, The Idle Race, no habían logrado mucho, excepto con los pocos fans más leales. Después, creo que Evil Woman [en 1975] fue “el” tema. Lo escribí tan rápido. Ahí fue cuando entendí de una vez cómo es la producción y la composición.

Cuando ELO estuvo en su punto más álgido a fines de los 70, ¿te preocupó que no tuvieras la personalidad para ser una estrella pop propiamente dicha?

– Probablemente. Porque no lo era y porque no pretendía serlo. No me considero estrella, sino cantautor, vocalista, productor y guitarrista. Puedo cantar bien, y también escribir temas.

Se sabe que odiabas tocar en vivo. ¿Era por el show o por todo lo demás que venía con eso?

– Sonaba para la mierda, ese era el problema. Los equipos de todos en ese entonces eran basura. Soy un productor, así que me puedo poner exquisito. No era malo… lo hago sonar como si hubiera sido espantoso. Simplemente no era lo que yo quería hacer.

¿Qué pasó con la nave espacial gigante que usaron en la gira de 1978?

– Creo que fue desarmada al final de la gira. Habría costado cientos de miles mantener la maldita cosa. Era un monstruo enorme. Era un poco un dolor de cabeza, realmente, porque tomaba dos días llevarlo de un lugar a otro, con lo que tendrías que hacer el show siguiente sin ella, y por supuesto la gente diría “¿Dónde está el platillo volador?”. Me imagino que estarían un poco desilusionados.

¿Alguna vez anduvo mal?

– Sí, cada tanto. Estábamos todos sobre plataformas hidráulicas y aparecíamos a través del escenario, pero alguna que otra vez se atascaba y lo único que podían ver era tu cabeza. “¡Sáquenme de aquí!”. Realmente vergonzoso.

Q Magazine nombró Livin’ Thing como su mayor “placer culposo”. ¿Te molesta ese concepto?

– Sí, porque en realidad es un tema muy inteligente. Pasa por dos relativas menores de un saque. No ves muchas así. Me gustaba el pop. No me gustaban las idas y vueltas pretenciosas de las canciones de 20 minutos de principios de los 80. Quería hacer temas lindos y concisos de tres minutos que tuvieran un buen sonido. El pop es para mí una de las formas más fuertes de la música, porque es tan difícil escribir una melodía que siga vigente luego de 40 años.

En Discovery, de 1979, abrazaron con éxito la música disco. ¿Alguna vez fuiste a los boliches?

– Sí, fui una vez a Studio 54 [célebre disco de Nueva York]. Estaba bien, supongo. Estaba lleno de estrellas de cine y ese tipo de gente. Me gustó el cuatro por cuatro, básicamente. El bombo haciendo bang, bang, bang, bang.

¿Qué canción fue la que te dio más dinero?

– Probablemente Mr. Blue Sky. Ha estado en un montón de películas, y pagan fortunas. Cuando la escribí [en un chalet suizo] había habido mucho niebla, y estaba arriba en la montaña. No había podido ver nada por una semana ni armar ningún tema. Después salió el sol, y escribí Mr. Blue Sky como un chiste. Resultó ser una muy linda canción.

Cuando disolviste ELO en 1986, ¿la idea era moverse hacia la producción?

– No tenía nada planeado particularmente, pero George Harrison me contactó y me pidió que produjera su álbum Cloud Nine. Tom Petty se enteró y me frenó en la calle en Los Ángeles y me dijo: “Ey, Jeff. ¿Te gustaría que escribamos canciones juntos?”. Descubrí que podía ser un gran colaborador. No era como lo imaginaba. Y por supuesto Full Moon Fever fue un gran, gran éxito. Sigue siendo el álbum favorito que hice.

¿Cuál de los miembros de The Travelling Wilburys contaba los mejores chistes?

– Roy Orbison. Tenía la risa más maravillosa que escuché. Era aguda, así que era como una risita. Podía hacer un sketch de Monty Python él solo, todas las partes, y después se caía riéndose de sí mismo.

Cuando te pidieron que produjeras el “nuevo” single de los Beatles Free as a Bird en 1995, ¿tuviste que callar al fan interno y dejar que el profesional se haga cargo?

– Siempre voy a ser el fan. Nos pasamos todo el primer día recordando, solo George, Paul [McCartney], Ringo [Starr] y yo, sentados alrededor de una mesa riéndonos, contando historias de los viejos tiempos. Las cuales no puedo contar, por supuesto. Algunas eran groseras. El solo hecho de estar ahí fue suficiente. Lo otro daba un poco de miedo. Hacer un disco de un cassette con la voz y el piano de John [Lennon] pegados juntos en mono. Lo hice a las dos o tres de la mañana porque no quería arruinarlo y que ellos estuvieran diciendo “Ja, ja, ¡no podés!”. Al día siguiente Paul vino corriendo y me dijo “¡Lo lograste! ¡Bien hecho!”, y me dio un gran abrazo. Fue lo mejor que podría haber pasado.

¿Es cierto que en 1968 fuiste testigo de la grabación del White Album de los Beatles?

– Sí, eso fue de lo más raro. Vi a Paul y a Ringo en el Estudio Uno haciendo Why Don’t We Do It In The Road. Y de ahí me fui al Estudio Dos y podía escuchar este tema que sonaba increíble. Era Glass Onion. Entramos, éramos el baterista de The Idle Race y yo. John y George nos saludaron. Y del otro lado de la ventana estaba George Martin, saltando de aquí para allá conduciendo las cuerdas. No pude dormir por semanas después de eso.

¿Tu madre nunca te dijo que es de mala educación usar anteojos de sol en interiores?

– No, lo que dijo fue “Parecías un desastre en la televisión”, y entonces inmediatamente me puse los anteojos porque no quería ser eso. Había estado toda la noche tomando, supongo. Siempre hablaba de las bolsas de mis ojos. Por eso siempre los uso. La gente debió pensar “Se convirtió en un idiota ostentoso con sus anteojos de sol a la noche”, pero no era por eso. Simplemente no quería mostrar mis bolsas.

When I Was a Boy (2015) describe tus sueños de chico de convertirte en un músico. ¿Conseguiste todo lo que querías?

– Sí, en cierto modo. Es como medio raro conseguir todo lo que querés. Y ha pasado a lo largo de los años. Todo lo que quise ha venido hacia mí: los Wilburys, los Beatles… así que es fantástico. No podría pedir más.

ELOSPAIN:

More than two years ago, Dorian Lynskey conducted an interview with JEFF LYNNE for Billboard that we bring to our website today, because we consider it interesting for any ELO/JEFF fan.

Electric Light Orchestra paid off an outstanding debt: finally inducted into the Rock & Roll Hall of Fame, along with Pearl Jam, Journey, Joan Baez, Tupac Shakur and Yes. With that excuse, we share this interview with Jeff Lynne, who reviewed some key moments of his career.

There is no pop legend more composed and frontal than Jeff Lynne. Sitting in the library of a venerable London hotel, his pleasant Birmingham, England accent intact despite living in Beverly Hills for 20 years (after two marriages, he is currently dating Camelia Kath, the ex-wife of actor Kiefer Sutherland). , still has the look of an extraordinarily prosperous lead from the 80s: lanky hair, a beard and sunglasses.

Lynne's 69-year-old genial normality means he was never exactly a pop star, even as Electric Light Orchestra (ELO) – the band he formed as sole songwriter and producer in 1970 – was on a roll with his quartet of strings. ELO smashed 18 Top 40 singles on the Billboard Hot 100. Between 1972 and 1986, they sold out arenas and dominated a yearning, opulent, retro-futuristic style of pop, whose fans include Daft Punk, The Flaming Lips, director David O. Russell and Ed Sheeran, with whom Lynne did a duetat the 2015 Grammys.

When Lynne disbanded ELO in 1986, he happily moved into the co-songwriter/producer chair for the likes of Tom Petty, Roy Orbison and the three remaining Beatles, also becoming the most modest member of babyboomer supergroup The Traveling Wilburys, sharing the bill with Petty, Orbison, Bob Dylan and George Harrison.

In 2015, he returned as Jeff Lynne's ELO with the release of his first album in 14 years, Alone in the Universe – the latest pleasant surprise in a career filled with that sort of thing. "Obviously everyone is going out to do it if they can," he says, "and I was lucky to do it well."

How would you synthetically define ELO?

- A normal band with two cellos and a violin. The strings usually clicked because there were no microphones in those days. They used to run all over the stage like crazy, playing them out of the air, so the tuning was awful, but it was a good show. They were running around with these gigantic bastards at the end of the stage, it's a surprise that no one ended up getting through.

ELO is back in style now, but when were they the furthest from that?

- Ten or fifteen years ago. We wanted to do a couple of shows, but there was no interest. All of that changed in the last six years. I think a lot of people realized that what I was doing wasn't mindless pop. It was smart pop.

When did you realize you could write a hit?

- I suppose it must have been with 10538 Overture [in 1972]. I was pleased with that. I remember thinking “Wow, I can really write a song”, because I didn't think I could. TheRecords by my old band, The Idle Race, hadn't achieved much except with the few most loyal fans. Later, I think Evil Woman [in 1975] was “the” theme. I wrote it so fast. That's when I understood at once what production and composition are like.

When ELO was at its peak in the late '70s, did you worry that you didn't have the personality to be a proper pop star?

- Probably. Because it wasn't and because it didn't pretend to be. I don't consider myself a star, but a singer-songwriter, vocalist, producer and guitarist. I can sing well, and also write songs.

It is known that you hated playing live. Was it for the show or for everything else that came with it?

- It sounded like shit, that was the problem. Everyone's equipment back then was crap. I'm a producer, so I can get fancy. It wasn't bad… I make it sound like it was awful. It just wasn't what I wanted to do.

What happened to the giant spaceship they used on the 1978 tour?

- I think it was disarmed at the end of the tour. It would have cost hundreds of thousands to maintain the damn thing. It was a huge monster. It was a bit of a headache, really, because it took two days to get it from one place to another, so you'd have to do the next show without her, and of course people would say "Where's the flying saucer?" I imagine they would be a little disappointed.

Was it ever wrong?

- Yes, every once in a while. We were all on hydraulic platforms and we would appear through the stage, but every once in a while it would get stuck and all they could see was your head. "Get me out of here!". Really embarrassing.

Q Magazine named Livin' Thing as their biggest "guilty pleasure." Does that concept bother you?

- Yes, because it is actually a very intelligent topic. It goes through two relative minors from a serve. You don't see many like that. I liked pop. I did not like the pretentious back and forth of the20-minute songs from the early 80s. I wanted to make nice, concise three-minute songs that had a good sound. Pop is for me one of the strongest forms of music, because it is so difficult to write a melody that is still relevant after 40 years.In 1979's Discovery, they successfully embraced disco music. Have you ever gone to the bowling alleys?

- Yes, I went to Studio 54 [a famous New York disco] once. It was fine I guess. It was full of movie stars and that kind of people. I liked the four by four, basically. The hype going bang, bang, bang, bang.

What song was the one that gave you the most money?

- Probably Mr. Blue Sky. He's been in a ton of movies, and they pay fortunes. When I wrote it [in a Swiss chalet] it had been very foggy, and I was up on the mountain. I hadn't been able to see anything for a week or put together any topic. Then the sun came up, and I wrote Mr. Blue Sky as a joke. It turned out to be a very nice song.

When you dissolved ELO in 1986, was the idea to move into production?

-I didn't have anything particularly planned, but George Harrison contacted me and asked me to produce his Cloud Nine album. Tom Petty found out and stopped me on the street in Los Angeles and said, “Hey, Jeff. Would you like us to write songs together?” I discovered that he could be a great collaborator. It wasn't how I imagined it. And of course Full Moon Fever was a big, big hit. It's still my favorite album I've ever made.

Which member of The Traveling Wilburys told the best jokes?

-Roy Orbison. He had the most wonderful laugh I ever heard. It was high pitched, so it was like a giggle. He could do a Monty Python skit by himself, all the parts, and then he'd fall over laughing at himself.

When you were asked to produce the “new” Beatles single Free as a Bird in 1995, did you have to shut down the inner fan and let the professional take over?

- I will always be the fan. We spent the whole first dayremembering, just George, Paul [McCartney], Ringo [Starr] and I, sitting around a table laughing, telling stories of the old days. Which I can't count, of course. Some were rude. Just being there was enough. The other was a little scary. Make a record from a cassette with John [Lennon's] voice and piano glued together in mono. I did it at two or three in the morning because I didn't want to mess it up and have them go “Ha ha, you can't!” The next day Paul came running to me and said “You did it! Well done!”, and he gave me a big hug. It was the best thing that could have happened.

Is it true that in 1968 you witnessed the recording of the Beatles' White Album?

- Yeah, that was weird. I saw Paul and Ringo in Studio One doing Why Don't We Do It In The Road. And from there I went to Studio Two and I could listen to this song that sounded incredible. It was Glass Onion. We walked in, it was the drummer from The Idle Race and me. john and georgethey greeted us. And on the other side of the window was George Martin, jumping up and down leading the ropes. I couldn't sleep for weeks after that.

Did your mom ever tell you that it's rude to wear sunglasses indoors?

-No, what she said was “You looked like a disaster on TV”, and then I immediately put on my glasses because I didn't want to be that. I had been drinking all night, I guess. He was always talking about the bags under my eyes. That's why I always use them. People must have thought “he turned into a flashy idiot with his sunglasses at night”, but it wasn't because of that. I just didn't want to show my bags.

When I Was a Boy (2015) describes your childhood dreams of becoming a musician. Did you get everything you wanted?

- Yes, in a way. It's kind of weird getting everything you want. And it has happened over the years. Everything I wanted has come to me: the Wilburys, the Beatles… so it's fantastic. I could not ask for more.

There is no pop legend more composed and frontal than Jeff Lynne. Sitting in the library of a venerable London hotel, his pleasant Birmingham, England accent intact despite living in Beverly Hills for 20 years (after two marriages, he is currently dating Camelia Kath, the ex-wife of actor Kiefer Sutherland). , still has the look of an extraordinarily prosperous lead from the 80s: lanky hair, a beard and sunglasses.

Lynne's cool normalcy, 69, means he was never exactly a pop star, even though Electric Light Orchestra (ELO) - the band he formed as sole songwriter and producer on1970– was in glory with his string quartet. ELO smashed 18 Top 40 singles on the Billboard Hot 100. Between 1972 and 1986, they sold out arenas and dominated a yearning, opulent, retro-futuristic style of pop, whose fans include Daft Punk, The Flaming Lips, director David O. Russell and Ed Sheeran, with whom Lynne duetted at the 2015 Grammys.

When Lynne disbanded ELO in 1986, he happily moved into the co-songwriter/producer chair for the likes of Tom Petty, Roy Orbison and the three remaining Beatles, also becoming the most modest member of babyboomer supergroup The Traveling Wilburys, sharing the bill with Petty, Orbison, Bob Dylan and George Harrison.

In 2015, he returned as Jeff Lynne's ELO with the release of his first album in 14 years, Alone in the Universe – the latest pleasant surprise in a career filled with that sort of thing. "Obviously everyone is going out to do it if they can," he says, "and I was lucky to do it well."

How would you synthetically define ELO?

- A normal band with two cellos and a violin. The strings usually clicked because there were no microphones in those days. They used to run all over the stage like crazy, playing them out of the air, so the tuning was awful, but it was a good show. They were running around with these gigantic bastards at the end of the stage, it's a surprise that no one ended up getting through.

ELO is back in style now, but when were they the furthest from that?

- Ten or fifteen years ago. We wanted to do a couple of shows, but there was no interest. All of that changed in the last six years. I think a lot of people realized that what I was doing wasn't mindless pop. It was smart pop.

When did you realize you could write a hit?

- I suppose it must have been with 10538 Overture [in 1972]. I was pleased with that. I remember thinking “Wow, I can really write a song”, because I didn't think I could. TheRecords by my old band, The Idle Race, hadn't achieved much except with the few most loyal fans. Later, I think Evil Woman [in 1975] was “the” theme. I wrote it so fast. That's when I understood at once what production and composition are like.

When ELO was at its peak in the late '70s, did you worry that you didn't have the personality to be a proper pop star?

- Probably. Because it wasn't and because it didn't pretend to be. I don't consider myself a star, but a singer-songwriter, vocalist, producer and guitarist. I can sing well, and also write songs.

It is known that you hated playing live. Was it for the show or for everything else that came with it?

- It sounded like shit, that was the problem. Everyone's equipment back then was crap. I'm a producer, so I can get fancy. It wasn't bad… I make it sound like it was awful. It just wasn't what I wanted to do.

What happened to the giant spaceship they used on the 1978 tour?

- I think it was disarmed at the end of the tour. It would have cost hundreds of thousands to maintain the damn thing. It was a huge monster. It was a bit of a headache, really, because it took two days to get it from one place to another, so you'd have to do the next show without her, and of course people would say "Where's the flying saucer?" I imagine they would be a little disappointed.

Was it ever wrong?

- Yes, every once in a while. We were all on hydraulic platforms and we would appear through the stage, but every once in a while it would get stuck and all they could see was your head. "Get me out of here!".

Really embarrassing.Q Magazine named Livin' Thing as their biggest "guilty pleasure." Does that concept bother you?

- Yes, because it is actually a very intelligent topic. It goes through two relative minors from a serve. You don't see many like that. I liked pop. I did not like the pretentious back and forth of the20-minute songs from the early 80s. I wanted to make nice, concise three-minute songs that had a good sound. Pop is for me one of the strongest forms of music, because it is so difficult to write a melody that is still relevant after 40 years.In 1979's Discovery, they successfully embraced disco music.

Have you ever gone to the bowling alleys?

- Yes, I went to Studio 54 [a famous New York disco] once. It was fine I guess. It was full of movie stars and that kind of people. I liked the four by four, basically. The hype going bang, bang, bang, bang.

What song was the one that gave you the most money?

- Probably Mr. Blue Sky. He's been in a ton of movies, and they pay fortunes. When I wrote it [in a Swiss chalet] it had been very foggy, and I was up on the mountain. I hadn't been able to see anything for a week or put together any topic. Then the sun came up, and I wrote Mr. Blue Sky as a joke. It turned out to be a very nice song.

When did you dissolve ELO in 1986, the idea was to move towards production?

-I didn't have anything particularly planned, but George Harrison contacted me and asked me to produce his Cloud Nine album. Tom Petty found out and stopped me on the street in Los Angeles and said, “Hey, Jeff. Would you like us to write songs together?” I discovered that he could be a great collaborator. It was not how he imagined it. And of course Full Moon Fever was a big, big hit. It's still my favorite album I've ever made.

Which member of The Traveling Wilburys told the best jokes?

-Roy Orbison. He had the most wonderful laugh I ever heard. She was sharp, so it was like a giggle. He could do a Monty Python skit by himself, all the parts, and then he'd fall over laughing at himself.

When you were asked to produce the “new” Beatles single Free as a Bird in 1995, did you have to shut down the inner fan and let the professional take over?

- I will always be the fan. We spent the whole first day reminiscing, just George, Paul [McCartney], Ringo [Starr] and I, sitting around a table laughing, telling stories of the old days. Which I can't count, of course. Some were rude. Just being there was enough. The other was a little scary. Make a record from a cassette with John [Lennon's] voice and piano glued together in mono. I did it at two or three in the morning because I didn't want to mess it up and have them be like, “Ha ha, no!you can!" The next day Paul came running to me and said “You did it! Well done!”, and he gave me a big hug.

It was the best thing that could have happened.Is it true that in 1968 you witnessed the recording of the Beatles' White Album?

- Yeah, that was weird. I saw Paul and Ringo in Studio One doing Why Don't We Do It In The Road. And from there I went to Studio Two and I could listen to this song that sounded incredible. It was Glass Onion. We walked in, it was the drummer from The Idle Race and me. John and George greeted us. And on the other side of the window was George Martin, jumping up and down leading the ropes. I couldn't sleep for weeks after that.

Did your mom ever tell you that it's rude to wear sunglasses indoors?

-No, what she said was “You looked like a disaster on TV”, and then I immediately put on my glasses because I didn't want to be that. I had been drinking all night, I guess. She was always talking about the bags under my eyes. That's why they alwaysuse. People must have thought “he turned into a flashy idiot with his sunglasses at night”, but it wasn't because of that. I just didn't want to show my bags.

When I Was a Boy (2015) describes your childhood dreams of becoming a musician. Did you get everything you wanted?

- Yes, in a way. It's kind of weird getting everything you want. And it has happened over the years. Everything I wanted has come to me: the Wilburys, the Beatles… so it's fantastic. I could not ask for more.