«HELLO, Mr. RADIO» traducido

El pasado día 26 de diciembre de 2012, en la noticia que ofrecimos en esta misma web titulada «HELLO, Mr. RADIO», alguién comentó si habría quién se animase a traducir las cuatro páginas que incluían el artículo publicado en SOUND+VISION de enero de 2013.

Pues bién… IVÁN FERNÁNDEZ, colaborador nuestro en diferentes ocasiones se ha tomado el trabajo de realizar dicha traducción por cuenta propia para que la incluyamos en nuestra web.

Vaya desde ELO ESPAÑA nuestra gratitud y nuestro reconocimiento por su disposición y colaboración con nosotros. MUCHAS GRACIAS IVÁN.

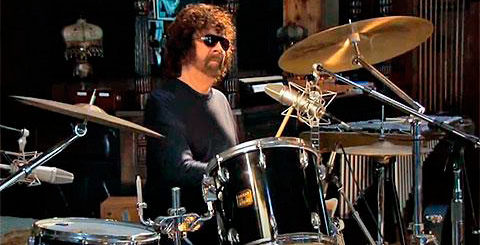

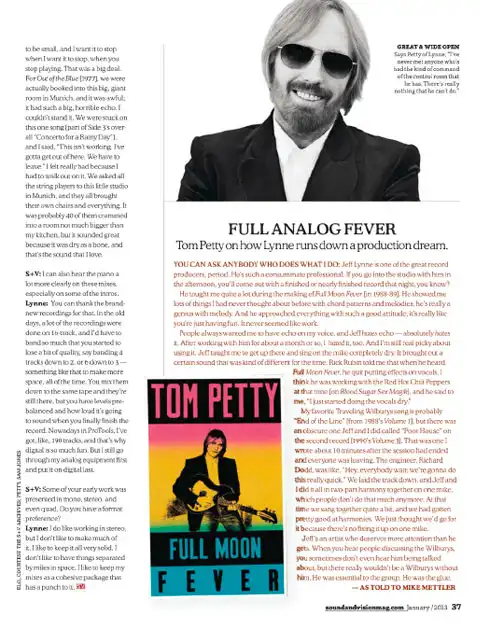

Entradilla: «JEFF tiene una tremenda inteligencia para el trabajo de estudio, pregúntale a cualquiera que haga música: él es uno de los mejores productores de música. Y punto». Eso dice TOM PETTY y si alguien lo sabe ese debe ser él. Habiendo trabajado con JEFF como productor en grandes éxitos comerciales como su propio «Full Moon Fever» y el «Volume 1″ de THE TRAVELING WILBURYS».

“En la época en la que muchos de nosotros estábamos metidos en bandas de garaje, él estaba en su casa con un grabador multipistas” apunta PETTY “ese siempre ha sido su verdadero amor, más que actuar está interesado en la grabación y en cómo hacerlas”.

LYNNE, de 65 años trabajador nato, multiinstrumentista y compositor, guió la mítica carrera de ELO en los 70 y los 80 y ahora ha vuelto con 2 álbumes:

1- Regrabaciones completas hechas por si mismo de una docena de clásicos en «Mr. BLUE SKY, THE VERY BEST OF ELO» y otras revisadas o editadas partes de 11 canciones ampliamente conocidas en «LONG WAVE» (ambas de la productora FRONTIERS).

¿Por qué volver a grabar tu propio material en Mr. BLUE SKY?

“Quería dejarlo igual“ reconoce “pero mejorando el sonido” Vaya…ahora queda claro…

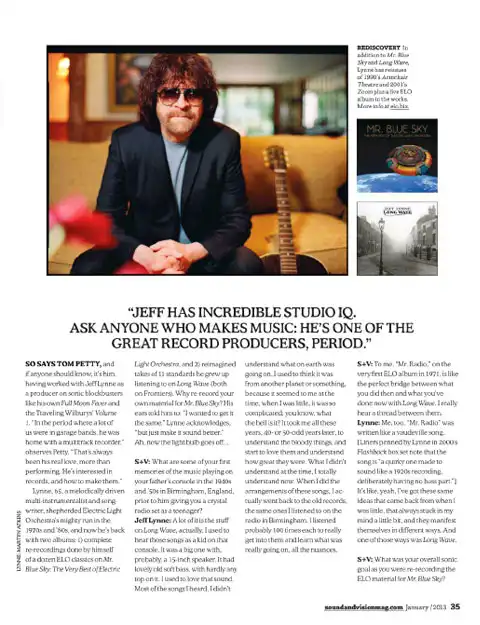

S+V: ¿Cuáles son algunos de tus primeros recuerdos sobre la música que sonaba en el equipo de tu padre en los 40 y 50 en Birmingham, Inglaterra, antes de que él te diera un equipo de radio cuando fuiste adolescente?

JL: Parte de ello es lo que aparece en LONG WAVE en realidad; yo solía escuchar esas canciones de crio en el equipo de mi padre que era muy grande con, probablemente, un altavoz de 15 pulgadas. Tenía unos encantadores y suaves bajos. Adoraba ese sonido.

No entendía la mayoría de canciones que escuchaba, solía pensar que era algo de otro planeta o algo así porque, en aquella época, me parecía muy complicado, ya sabes, yo decía “que demonios es esto”. Me costo todos esos años, 40-50 años, entender ese maldito material, empezar a amarlo y a entender como era de grande. Lo que no entendía completamente en esa época lo entiendo ahora. Cuando hice los preparativos para las canciones, en realidad volví a esos viejos temas que escuchaba en esa radio en Birmingham. Los escuche probablemente 100 veces cada uno para realmente meterme dentro de ellos y entender de qué iban, todos los matices.

S+V: Para mi, “Mr. Radio” en el primer álbum de ELO en 1971, es el puente perfecto entre lo que hiciste y lo que has hecho ahora con LONG WAVE. Realmente escucho un hilo conductor.

JL: Yo también. «Mr. Radio» fue escrita como una vaudeville (este nombre se utiliza para piezas cortas de música y actuación escritas a principios del siglo 20) de hecho al canción está hecha para que suene como una canción de los años 20, grabada a propósito sin partes con bajos. Es como; si, tengo estas ideas que me vuelven de cuando era pequeño, que siempre han estado un poco metidas en mi mente, y ellas mismas se manifiestan de diferentes maneras, una de esas maneras fue LONG WAVE.

S+V: ¿Cual era tu objetivo general en cuando a sonido cuando estuviste regrabando el material de ELO de Mr. Blue Sky?

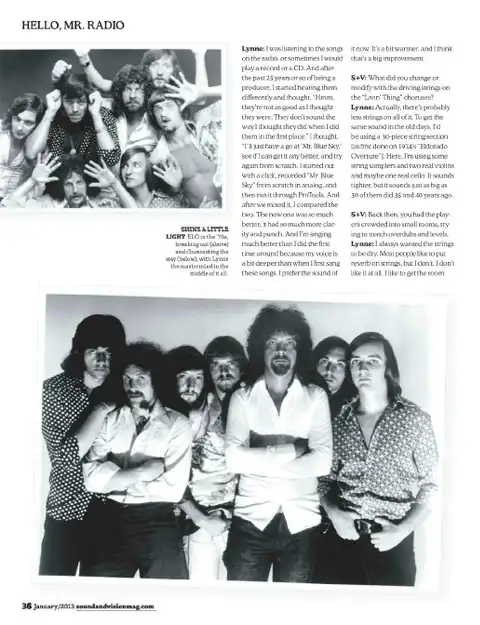

JL: Estaba escuchando las canciones en la radio o a veces ponía un disco y después de pasar estos 25 años siendo un productor empecé a escuchar esos temas de forma diferente y pensé “no son tan buenos como pensé que eran y no suenan como quería que sonasen cuando los hice la primera vez».

Así que me dije, voy a ir a por Mr. Blue Sky y ver si puedo hacer que suene mejor y probar otra vez de cero así que empecé con un clic regrabando Mr. Blue Sky de cero en analógico y después lo puse en PROTOOLS y después de que los mezcláramos los compare. El nuevo era mucho mejor, tenía mucha mas claridad y fuerza y además canto mucho mejor de lo que lo hice la primera vez por que ahora mi voz es mas profunda que cuando cante estas canciones por primera vez. Prefiero el sonido aactual, es más cálido y creo que eso es una gran mejora.

S+V: ¿Qué cambiaste o modificaste en los sonidos de cuerda en los coros de la canción “Livin Thin’s”?

JL: En realidad, probablemente hay menos cuerdas en todos ellos. Para conseguir el mismo sonido en los viejos tiempos yo usaría una sección de cuerdas de 30 piezas (como hice en Eldorado en 1974). Ahora, he usado un par de modelos de cuerdas, un par de violines reales y puede que un cello real. El sonido es más ajustado pero suena tan grande como el de 30 piezas que sonaba hace 35 y 40 años.

S+V: De vuelta a entonces, tú tenías a los artistas amontonados en pequeñas habitaciones, intentando conseguir los niveles y overdub (se refiere a los sonidos mezclados en una canción, los que suenan al fondo, como las bases, pero no se la traducción exacta al castellano).

JL: Siempre quería que las cuerdas sonaran secas, a mucha gente le gusta poner reverberación en las cuerdas pero a mi no. No me gusta en absoluto.

Me gusta tener una habitación pequeña, y quiero que pare cuando yo quiero que pare(se refiera a que el quiere que el sonido de sus grabaciones se detenga cuando el quiere, por lo que si unas cuerdas siguen sonado por reverberación o eco eso queda mal para el), es decir, cuando de se deja de tocar. Y eso era un gran desafío.

Para OUT OF THE BLUE en 1977, teníamos reservado este enorme, gigante estudio en Munich y era horrible, tenía un impresionante eco, no lo soportaba. Estábamos atascados en esta canción (parte del Concerto For a Rainy Day) y dije: esto no funciona, tengo que salir de aquí, tenemos que largarnos, me sentía realmente mal por que tenía que (walk out puede ser aguantar, pasar, pasar de algo…) así que les pedí que se metieran en un pequeño estudio en Munich y ellos se trajeron sus propias sillas y todo. Había probablemente 40 de ellos arrejuntados en una habitación no mucho mas grande que mi cocina pero sonaba genial por que sonaba seco como un hueso y ese es el sonido que a mi me encanta.

S+V: También puedo oír el piano mucho más claramente en estas mezclas, especialmente en algunas de las intros.

JL: Puedes darle las gracias a los flamantes nuevos grabadores de ahora. En los viejos tiempos un montón de esas grabaciones estaban hechas en 16 pistas y tenía que ajustarlo tanto que empezabas a perder algo de calidad, por ejemplo los de 4 pistas teníamos que ajustarlo en 2, o de 6 en 3, algo así para hacer más espacio durante todo el rato. Las pones en la misma cinta y aun están ahí pero tienes niveles preajustados y tienes también preajustado cómo de alto va a sonar cuando acabes con ello. Pero ahora, en protools, tengo sobre 190 pistas y esa es la razón por la que el sonido digital es tan divertido, pero aun así aún uso primero mi equipo y luego lo paso al digital.

S+V: Algunos de tus primeros trabajos estaban presentados en mono, estereo e incluso en quad, ¿tienes alguna preferencia de formato?

JL: Me gusta trabajar en stereo pero no me gusta hacerlo en exceso, me gusta mantenerlo todo muy sólido, no me gusta tener cosas separadas por millas de distancia, me gusta mantener mi mezcla como paquetes coherentes con fuerza.

ENTREVISTA A TOM PETTY

PUEDES PREGUNTARLE A CUALQUIER QUE HAGA LO QUE YO:

LYNNE es uno de los grandes productores de música. Punto. Es un increíble y consumado profesional. Si entras al estudio con él por la tarde, puedes estar seguro de que vas a salir de ahí con una grabación terminada o casi terminada por la noche.

Me enseño mucho durante la grabación de FULL MOON FEVER (en 1988-89) me mostró muchas cosas sobre las que yo no había pensado con anterioridad en cuanto a acordes y melodía. Y además lo hace todo con una gran actitud, es como si estuviera divirtiéndose o pasando un buen rato, nunca parecía como trabajo.

La gente siempre quería que tuviera eco en mi voz. Pero LYNNE odia el eco, lo odia completamente, y tras trabajar con él durante un mes o así yo también lo odié y aun soy bastante reticente a usarlo. JEFF me enseñó a llegar y cantar en el micrófono completamente seco. El sacó un sonido que era bastante diferente a todo lo que se escuchaba entonces. Rick Rubín me dijo que cuando escuchó FULL MOON FEVER dejó de poner efectos en las voces, creo que estaba trabajando con los Red Hot Chilly Pepper y me dijo “simplemente empecé a hacer las voces secas”.

Mi canción favorita de THE TRAVELING WILBURYS es probablemente «End of the Line» (1988 volume 1) pero había una bastante desconocida que JEFF y yo hicimos, llamada «Poor House» en el segundo disco (volume 3 de 1990) esa la escribí yo en 10 minutos después de que la sesión de grabación hubiera terminado y todo el mundo se estaba marchando. El ingeniero, Richard Dood estaba como todo el mundo esperado, «vamos a hacer esto realmente rápido” pusimos las pista y JEFF y yo la hicimos en una armonía con dos partes juntos en un solo micrófono. En aquel entonces cantábamos juntos de vez en cuando y nos habíamos vuelto bastante buenos con la armonía.

JEFF es un artista que se merece mucha más atención de la que tiene. Cuando oyes a gente hablar sobre los Wilburys, a veces JEFF ni siquiera es mencionado, pero no habría habido Wilburys sin él. Era esencial para el grupo. Era lo que nos mantenía unidos.

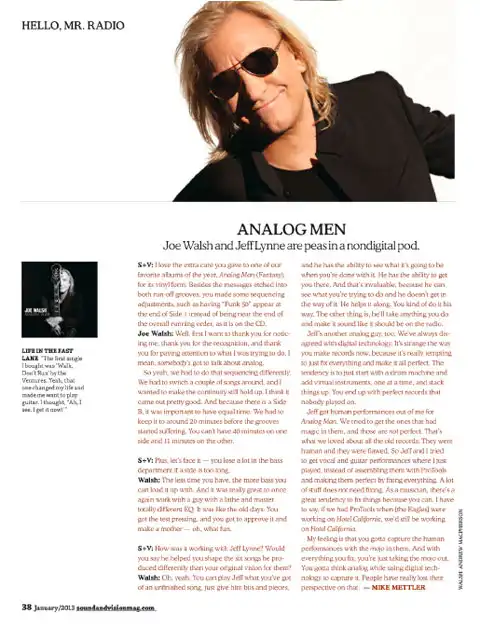

ENTREVISTA A JOE WALSH

S+V: Me encanta el cuidado especial que le prestaste a uno de nuestros álbumes favoritos del año, ANALOG MAN para su edición en vinilo. Además de los mensajes puestos en ambos «run off grooves» (podría tratarse de las líneas del vinilo, las que son leídas para que suene que por lo visto el puso algo ahí) así como ajustes en la secuenciación, como poner FUNK 50 al final de la parte 1 en lugar de estar al final del orden general, como está en el CD.

JW: Bueno, primero gracias por el reconocimiento y gracias por prestar atención a lo que estaba intentando hacer y quiero decir. Alguien llego a hablar sobre música analógica.

Y si, nosotros teníamos que hacer esa secuencia de forma diferente, teníamos que mover un par de canciones pero quería que la continuidad todavía se mantuviera. Creo que salí bastante bien. Y dado que hay una parte B, es importante tener la misma duración, teníamos que mantenerlo sobre los 20 minutos antes de que los surcos empezaran a sufrir (las líneas de vinilo). No puedes tener 40 minutos en una parte y 11 en otra.

S+V: Además, afrontémoslo, pierdes mucho en cuanto a bajos si una cara es demasiado larga.

JW: Cuanto menos tiempo pones más bajos puedes incluir y fue realmente maravilloso trabajar con un tío con un mezclador y un control de EQ completamente diferente. Tu tienes el voto de test y después lo apruebas y haces la raíz, muy divertido.

S+V: Y ¿como fué trabajar con JEFF LYNNE? ¿Dirías que te ayudó a darle forma a las 6 canciones que el produjo de forma diferente a tu visión original sobre ellas?

JW: Si, puedes tocar o jugar con JEFF sobre lo que tienes de una canción inacabada, simplemente darle trocitos, y él tiene la habilidad de ver como va a ser una vez la hayas terminado. Tiene la habilidad de llevarte ahí. Y eso no tiene precio, porque él puede ver lo que estas intentando hacer y no se mete en medio, además, él puede coger todo lo que hagas y hacerlo sonar como debería sonar en la radio.

JEFF es también otro tipo analógico, siempre hemos estado en desacuerdo con la tecnología digital, es raro como se hacen discos ahora; porque es realmente tentador coger todo, arreglarlo y ponerlo perfecto, la tendencia es empezar con una maquina/instrumento de percusión y añadir luego instrumentos virtuales, uno cada vez, y construir sobre ello. Acabas con discos perfectos que nadie pone.

JEFF tenía actuaciones humanas para ANALOG MAN cogimos las que tenían ”magia” y esas no son perfectas. Eso es sólo que nos gustaba sobre los viejos discos: eran humanas y tenían fallos, así que JEFF y yo intentamos tener voces y actuaciones de guitarra donde solíamos tocar (o como las solíamos tocar) en lugar de arreglarlas con protools y hacer todo perfecto. Mucho material no necesita arreglos o ediciones. Como músico, hay una gran tendencia a arreglar o modificar cosas simplemente porque puedes hacerlo. Si hubiéramos tenido protools cuando The Eagles tocaban «Hotel California» todavía estaríamos ahí.

Creo que debes capturar las actuaciones humanas que tienen pequeños defectos y con todo lo que arreglas o editas simplemente quitas eso de la canción. Tienes que pensar de forma analógica mientras estas usando tecnología digital para capturarlo. La gente ha perdido la perspectiva en cuanto a eso.

ELOSPAIN:

On December 26, 2012, in the news that we offered on this same website entitled "HELLO, Mr. RADIO", someone commented if there would be someone who dared to translate the four pages that included the article published in SOUND+VISION in January of 2013.

Well then… IVÁN FERNÁNDEZ, our collaborator on different occasions, has taken the trouble to carry out said translation on his own so that we can include it on our website.

Go from ELO ESPAÑA our gratitude and our appreciation for your willingness and collaboration with us. THANK YOU SO MUCH IVAN.

Intro: "JEFF has tremendous smarts for studio work, ask anyone who makes music: he's one of the best music producers. Period." So says TOM PETTY and if anyone knows that it must be him. Having worked with JEFF as a producer on major commercial hits such as his own "Full Moon Fever" and THE TRAVELING WILBURYS "Volume 1".

“At the time when a lot of us were into garage bands, he was at home with a multitrack recorder,” says PETTY, “that's always been his true love, more than acting he's interested in recording and how to make it. ”.

LYNNE, 65 years old hard worker, multi-instrumentalist and composer, guided the mythical career of ELO in the 70s and 80s and now he is back with 2 albums: 1- Complete re-recordings made by himself of a dozen classics on "Mr. BLUE SKY, THE VERY BEST OF ELO" and other revised or edited parts of 11 widely known songs on "LONG WAVE" (both fromthe production company FRONTIERS).

Why re-record your own material on Mr. BLUE SKY?

"I wanted to leave it the same" she admits "but improving the sound" Wow… now it's clear…

S+V: What are some of your earliest memories of the music playing on your father's equipment in the 1940s and 1950s in Birmingham, England, before he gave you a radio set as a teenager?

JL: Part of it is what actually appears in LONG WAVE; I used to listen to those songs growing up on my dad's computer which was really big with probably a 15 inch speaker. He had lovely smooth bass. He loved that sound. I didn't understand most of the songs I heard, I used to think it was something from another planet or something because, at that time, it seemed very complicated, you know, I was like “what the hell is this”. It took me all those years, 40-50 years, to understand that damn material, to start loving it and to understand how big it was. What I did not fully understand inI understand that time now. When I did the preparations for the songs, I actually went back to those old songs that I heard on that radio in Birmingham. I listened to them probably 100 times each to really get into them and understand what they were about, all the nuances.

S+V: For me, “Mr. Radio” on ELO's first album in 1971, is the perfect bridge between what you did and what you've done now with LONG WAVE. I really hear a common thread.

JL: Me too. "Mr. Radio" was written as a vaudeville (this name is used for short pieces of music and performance written in the early 20th century) in fact the song is made to sound like a 1920s song, recorded on purpose without parts with bass It is like; Yes, I have these ideas that come back to me from when I was little, that have always been a bit stuck in my mind, and they manifest themselves in different ways, one of those ways was LONG WAVE.

S+V: What was your overall sound-wise goal when you were re-recording the ELO material for Mr. Blue Sky?

JL: I was listening to the songs on the radio or sometimes I would put on a record and after spending these 25 years being a producer I started to listen to those songs differently and I thought “they're not as good as I thought they were and they don't sound like I wanted them to sound”. when I did them the first time." So I said to myself, I'm going to go for Mr. Blue Sky and see if I can make it sound better and try again from scratch so I started with a click re-recording Mr. Blue Sky from scratch on analogue and then I put it in PROTOOLS and after we mixed them I compared them. The new one was much better, it had much more clarity and strength and also I sing much better than I did the first time because now my voice is deeper than when i sing these songs for the first time i prefer the current sound, it's warmer and i think that's a big improvement

S+V: What did you change or modify in the sounds ofchord in the chorus of the song “Livin Thin's”?

JL: Actually, there are probably fewer strings on all of them. To get the same sound in the old days I would use a 30 piece string section (as I did on Eldorado in 1974). Now, I've used a couple of string models, a couple of real violins, and maybe a real cello. The sound is tighter but it sounds as big as the 30 piece that sounded 35 and 40 years ago.

S+V: Back then, you had the artists huddled together in little rooms, trying to get the levels and overdub (refers to the sounds mixed in a song, the ones that play in the background, like the bases, but you don't know it). exact translation into Spanish).

JL: I always wanted the strings to sound dry, a lot of people like to put reverb on the strings but I don't. I don't like it at all. I like having a small room, and I want it to stop when I want it to stop (meaning that he wants the sound of hisrecordings stop when he wants, so if some strings continue to sound due to reverberation or echo that looks bad for him), that is, when he stops playing. And that was a great challenge. For OUT OF THE BLUE in 1977, we had booked this huge, giant studio in Munich and it was horrible, it had an amazing echo, I couldn't stand it. We were stuck on this song (part of the Concerto For a Rainy Day) and I said: this is not working, I have to get out of here, we have to get out of here, I felt really bad that I had to (walk out can be hold, walk out, walk out something…) so I asked them to go into a little studio in Munich and they brought their own chairs and everything. There were probably 40 of them crammed into a room not much bigger than my kitchen but it sounded great because it sounded dry as a bone and that's the sound I love.

S+V: I can also hear the piano much more clearly in these mixes, especially in some of the intros. JL: You can thank the brand new recorders of today. In the old days a lot of those recordings were made on 16 tracks and you had to adjust it so much that you started to lose some quality, for example the 4 tracks we had to adjust it to 2, or 6 to 3, something like that to make more space all the time. You put them on the same tape and they're still there but you have preset levels and you also have preset how loud it's going to be when you're done with it. But now, in protools, I have over 190 tracks and that's why digital sound is so much fun, but still I still use my rig first and then switch to digital.

S+V: Some of your early works were presented in mono, stereo and even quad. Do you have any format preferences?

JL: I like to work in stereo but I don't like to do it excessively, I likekeep it all very solid, I don't like to have things miles apart, I like to keep my mix as tightly cohesive packages.

INTERVIEW WITH TOM PETTY

YOU CAN ASK ANYONE TO DO WHAT I DO:

LYNNE is one of the great music producers. Spot. He is an incredible and consummate professional. If you walk into the studio with him in the afternoon, you can be sure you'll walk out with a finished or nearly finished recording by night.

He taught me a lot during the recording of FULL MOON FEVER (in 1988-89) he showed me a lot of things that I hadn't thought about before in terms of chords and melody. And also he does everything with a great attitude, it's like he's having fun or having a good time, it never seemed like work. People always wanted it to have an echo in my voice. But LYNNE hates the echo, absolutely hates it, and after working with it for a month or so I hated it too and am still pretty reluctant to use it. Jeff taught me toarrive and sing into the microphone completely dry. He he put out a sound that was quite different from anything heard back then. Rick Rubin told me that when he heard FULL MOON FEVER he stopped putting effects on the vocals, I think he was working with Red Hot Chilly Pepper and he told me “I just started doing the dry vocals”. My favorite song from THE TRAVELING WILBURYS is probably "End of the Line" (1988 volume 1) but there was a rather unknown one that JEFF and I did called "Poor House" on the second record (volume 3 from 1990) I wrote that in 10 minutes after the recording session had ended and everyone was leaving. The engineer, Richard Dood was as everyone expected, “we're going to do this real quick” we laid the track down and JEFF and I did it in a harmony with two parts together on one mic. Back then we sang together from time to time and we had gotten pretty good with harmony JEFF is aartist who deserves much more attention than he gets. When you hear people talk about the Wilburys, sometimes JEFF isn't even mentioned, but there would have been no Wilburys without him. He was essential to the group. It was what held us together.

INTERVIEW WITH JOE WALSH

S+V: I love the extra care you gave to one of our favorite albums of the year, ANALOG MAN for its vinyl release. In addition to the messages placed on both "run off grooves" (could be the lines on the vinyl, which are read to make it sound like he put something there) as well as sequencing adjustments, such as putting FUNK 50 at the end from part 1 instead of at the end of the general order, as it is on the CD.

JW: Well first thanks for the acknowledgment and thanks for paying attention to what I was trying to do and I mean. Someone came to talk about analog music. And yes, we had to do that sequence differently, we had to move a couple of songs but I wanted the continuity to still hold. I think I came out pretty good. And since there's a B part, it's important to have the same length, we had to keep it over 20 minutes before the grooves started to suffer.(the vinyl lines). You can't have 40 minutes in one part and 11 in another.

S+V: Also, let's face it, you lose a lot in terms of bass if a face is too long.

JW: The less time you put in the more bass you can include and it was really cool to work with a guy with a completely different mixer and EQ control. You get the test vote and then you approve it and do the root, so much fun.

S+V: And how was it working with JEFF LYNNE? Would you say that he helped you to shape the 6 songs that he produced differently from your original vision of them?

JW: Yeah, you can play or play with JEFF on what you have of an unfinished song, just give it bits and pieces, and he has the ability to see what it's going to be like once you've finished it. He has the ability to take you there. And that's priceless, because he can see what you're trying to do and stay out of the way, plus he can take everything you do and make it sound like it should sound on the radio. jeff is alsoanother analog guy, we've always disagreed with digital technology, it's weird how records are made now; Because it's really tempting to take everything, fix it and make it perfect, the tendency is to start with a machine/percussion instrument and then add virtual instruments, one at a time, and build on it. You end up with perfect records that no one plays. JEFF had human performances for ANALOG MAN we took the ones with "magic" and those are not perfect. That's just what we liked about the old records: they were human and flawed, so JEFF and I tried to have vocals and guitar performances where we used to play (or how we used to play them) instead of fixing them with protools and making everything perfect. Much material does not need fixing or editing. As a musician, there's a big tendency to fix or tweak things just because you can. If we had protools when The Eagles played "Hotel California" we would still be there. I think thatyou have to capture human performances that have little flaws and with everything you fix or edit you just take that out of the song. You have to think in analog while you're using digital technology to capture it. People have lost perspective on that.